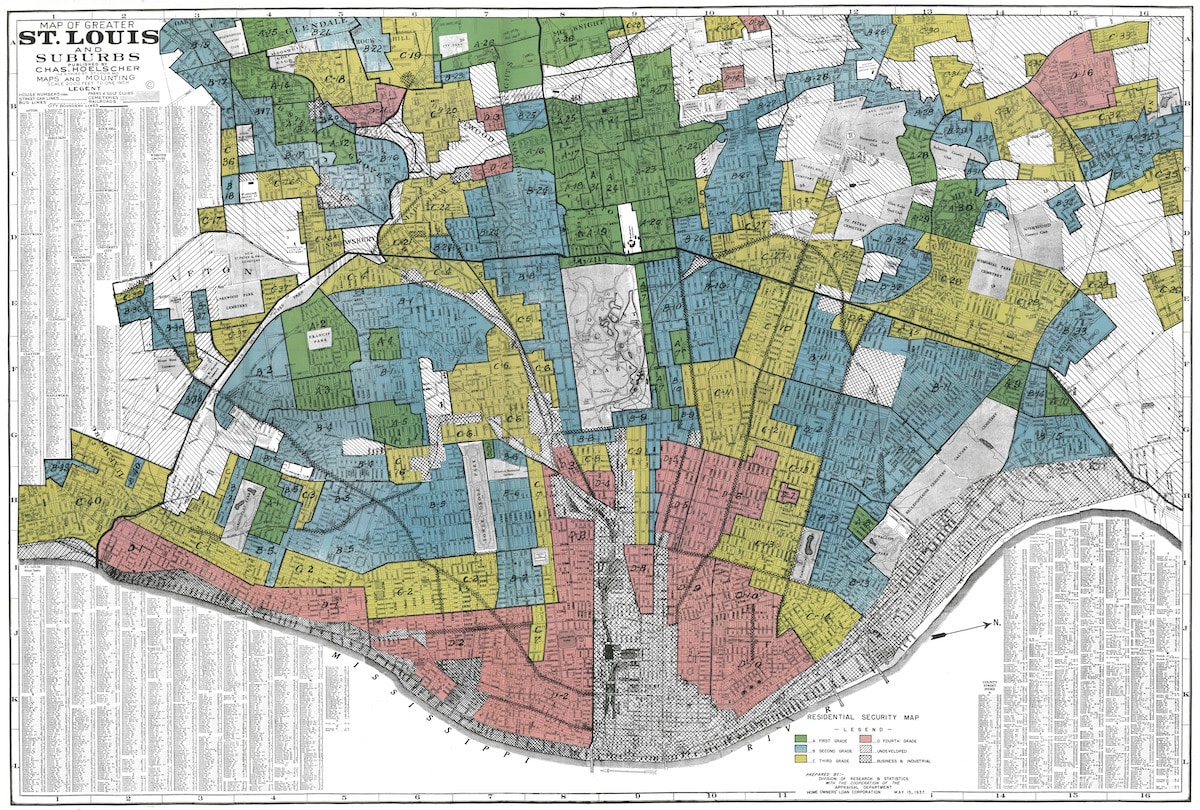

In 1976, historian Kenneth T. Jackson discovered a decades-old, previously secret government document that displayed visual proof of America’s racist housing policies in the 1930s and beyond, using a discriminatory practice later known as redlining.

Redlining began during the Great Depression, at a time when the government created homeownership programs to stimulate the economy. As part of the program, FDR’s administration funded government-backed mortgages for homeowners, a form of federal aid designed to stop a tsunami of foreclosures. The homeownership programs successfully saved many homeowners from foreclosing on their homes, but not everyone benefited equally — or at all.

The government created criteria for appraising properties and evaluating homeowners who may qualify as a way of determining lending risk. They rated the risk of neighborhoods in over 200 cities across America, with each neighborhood assigned one of four color-coded rankings. However, bureaucrats kept the specifics of these criteria secret from the American public for decades.

Although black Americans already knew that the country’s lending practices were racist, Jackson’s discovery in 1976 showed visual proof that the government’s housing policies were far from fair and balanced. One day, when he was searching for unrelated housing records, he found a color-coded map of St. Louis from 1937, ranking every neighborhood in the city based on how qualified the residents there were of receiving a mortgage.

The map color-coded the neighborhoods into four categories, from least to most risky:

- Green: First Grade

- Blue: Second Grade

- Yellow: Third Grade

- Red: Fourth Grade

Coincidentally, nearly all Black St. Louis residents lived in a red zone. As researchers discovered more maps of other American cities like New York, Atlanta, Philadelphia, Cleveland, and Detroit, they saw similar patterns everywhere. The vast majority of black Americans lived in a red zone. Racial steering (the practice of real estate agents turning away minorities) and segregation practices made it nearly impossible for them to move to a higher-rated neighborhood.

Appraisers who evaluated mixed-race neighborhoods rated them poorly due to what they called “colored infiltration.” If black people moved into a white neighborhood, white neighbors feared that their property values would decline, so both legal and de facto segregation became the norm. Public and private lenders used the color-coded maps, so black Americans in St. Louis and all over the country were effectively banned from obtaining home loans.

In addition to redlining, the United States government implemented other racist housing policies, such as The Federal Housing Administration’s (FHA’s) 1936 Underwriting Manual. The manual banned black Americans from receiving home loans. It mandated segregation in most neighborhoods, even going as far as using highways and walls to physically cut off black neighborhoods from the rest of the city. As a result, a huge percentage of African Americans ended up in large urban housing projects over the coming decades.

The Civil Rights Act of 1968 included the Fair Housing Act, which outlawed segregationist and racist housing practices. However, the effects of redlining and similar policies still linger today. By the time Fair Housing Act passed, many homes were no longer affordable for Black Americans, who were not afforded the same opportunity to accumulate wealth through homeownership like white Americans. Many neighborhoods remained highly segregated for decades, with most remaining segregated to this day.

Inequality in Housing Persists

Owning and building equity in a home is the primary way Americans create lasting wealth that affects future generations. For Americans who own a house, more than half of their net worth is in their home equity. Although it’s officially been illegal for decades, redlining policies that unfairly shut out millions of black Americans from obtaining mortgages still impact inequities in modern America. In 2019, the U.S Census reported that homeownership in America was 64.6%. 73.3% of white Americans owned a home, compared to only 42.1% of black Americans, a 31 point difference.

The disparities in homeownership are a major contributing factor to the racial wealth gap. While 13% of America’s population is black, African American households hold only 3% of the country’s wealth. Data released by the Federal Reserve Board’s Regulation C following the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) shows that Black applicants were almost twice as likely to be denied a mortgage than white applicants, reinforcing and exacerbating existing inequities in homeownership. While America made efforts to address the racial sins of the past, there’s evidence to show that the racial wealth gap is only worsening.

Modern America: Still Separate, Still Unequal

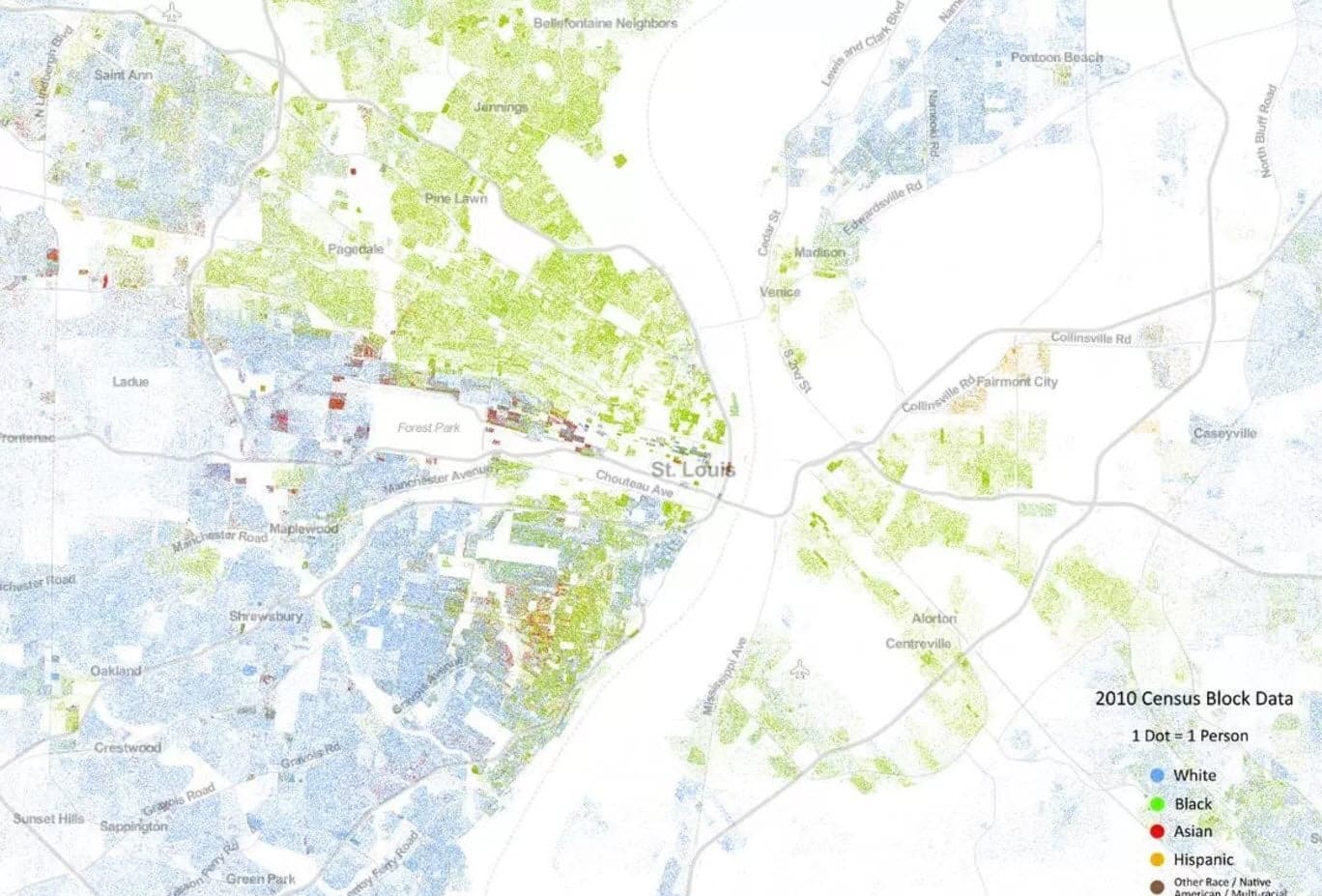

Even though segregation formally ended in the 1960s, residential segregation persists in modern America. The country is far more diverse than in the 1960s, but racial segregation between white and black Americans only modestly decreased over the last 60 years.

The best way to visualize this segregation is through a map, using St. Louis as an example. According to the census, the St. Louis metro area (including the city and surrounding suburbs) is around 73% white and 18% black, with the remaining 9% identifying as Latino, Asian, or other. Despite the area’s moderate level of diversity, the vast majority of white and black residents live in highly segregated neighborhoods.

View the racial dot map of St. Louis below to see a shocking visual of segregation. Blue represents white residents, and green represents black residents. As you can see, black residents remain segregated to only a small portion of the central metro area, while white residents live in the remaining outlying suburbs.

Few truly racially mixed neighborhoods exist in the St. Louis area, but the racial dot map only tells part of the story. Even though we are deep into the 21st century, inequality in wealth, housing, and education between white and black neighborhoods in St. Louis is in many ways just as stark now as it was in the 1930s.

St. Louis isn’t an outlier either, as racial segregation and inequality persists in every major American city. Even stereotypically progressive cities like New York remain highly segregated and unequal. NYC ranked as the fourth most segregated big city in America, and New York state had the most segregated school system for black students.

In the wake of the George Floyd protests, some municipalities decided to take actionable steps to reduce racial segregation and inequality. Asheville, NC, for example, approved funds for reparations, with an emphasis on increasing black homeownership in the city.